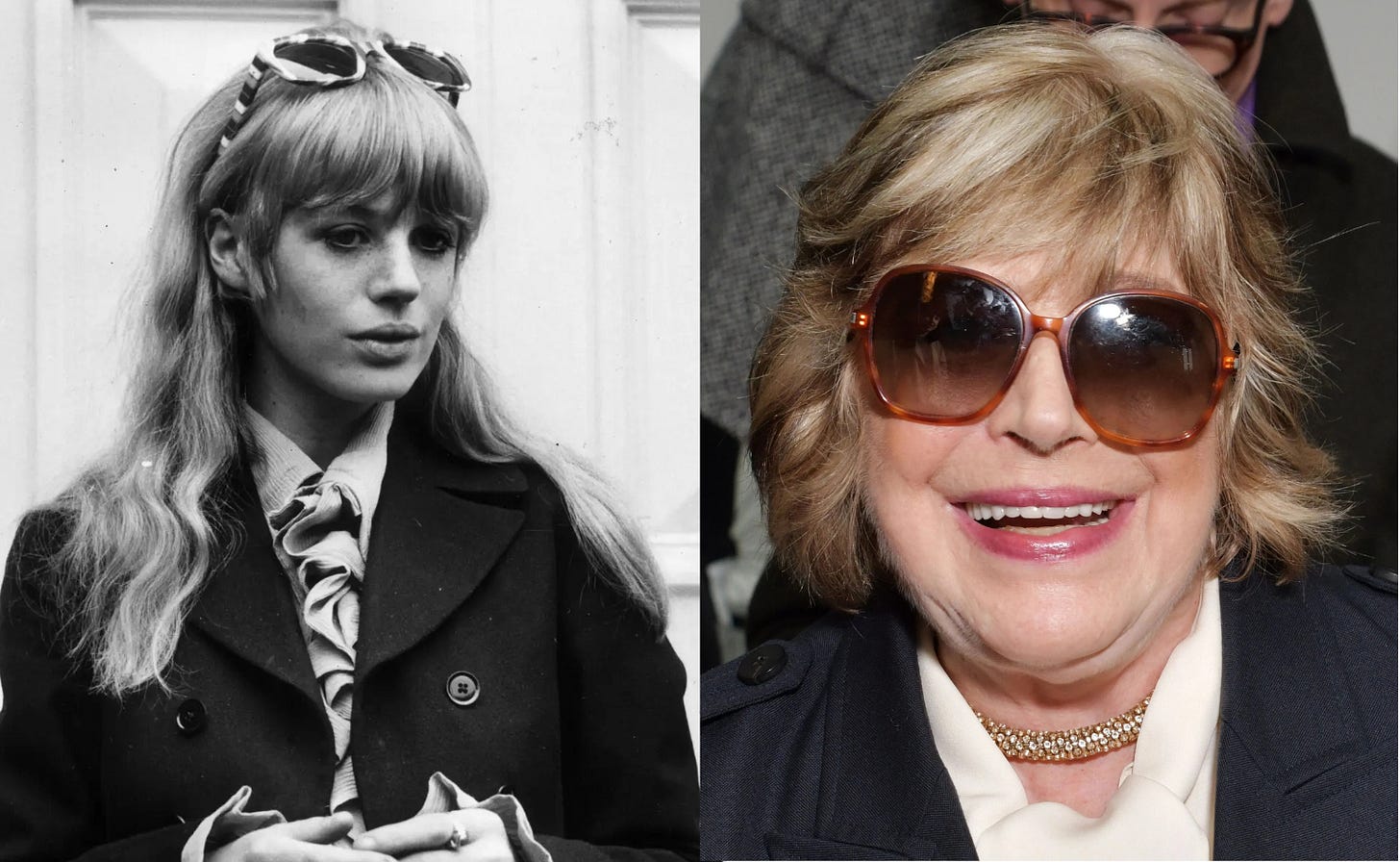

Remembering Marianne Faithfull*, but not as she actually was

The pictures chosen for obituaries are yet more evidence that society would prefer it if women stopped ageing at 40 (max)

This time last week (give or take a day) I was trying to choose a picture of Marianne Faithfull to lead my weekly Links & Recs post. And I could already feel my gears grinding. The obituaries were coming thick and fast, as they should, when someone of her stature, talent and cultural importance dies. But, almost without exception, the Marianne of their dreams was 25. The New York Times, Guardian, NPR, Sky, Harpers Bazaar, BBC News, Irish Times, People, The Spectator, I would go on but life’s too short. Many of them were generous with their words (although almost every single one of them mentioned Mick Jagger very near the top, that’s OK, I can live with that), not a single one of them had any interest in remembering Marianne Faithfull as she actually looked, at least through the second part of her life. Only as she had been, many decades ago. Lithe, blonde, slim, stunning. (Also anorexic and suffering from heroin addiction, but details schmetails.)

Like I say, my gears were grinding when Sophie Heawood (

) posted this on notes: “Someone I’m Facebook friends with…was close to Marianne Faithfull. He has posted some lovely recent photos of her, in which she is grinning from her wheelchair, out and about with her pal, looking like you’d expect someone to look if they were unwell and in their late 70s, with the figure to match. Her smile! The bowl cut! These are bloody LOVELY pictures!“Obviously I can’t repost them here because they’re not mine, but it was so startling to see them while the rest of my timeline filled up with the young, thin, drugged and probably miserable version of Marianne from fifty years ago. I so preferred seeing the person she was at the end of her life, and how she made it through, and seemed to be really enjoying herself.”

Yes! Yes! Yes!

This hit me right in the guts because it’s something I think about every time a woman in the public eye dies and I start searching the internet for a picture to commemorate her in the Friday round-up. And it always – without fail – goes a bit like this:

Google obituaries. Wonder if I’ve gone mad and said person actually died at the age of 25/30/35. Because almost every single media outlet has used a picture of her at that age. Get angry. Start hunting for pictures of them at around the age they died. Get more angry.

Hands up, it is almost always easier to find an iconic – for which 99 times out of 100 read young, often black and white – picture, and, I know, picture editors are busy, busy people.

But it is also always (and I do mean always) possible to find a contemporary-ish picture if you just put in a tiny bit more groundwork. (And, it could be my imagination, but I don’t think it is, they often look so much more… gleeful in the later pictures.) So I can only assume that whoever is doing the choosing looks at the pictures and decides that, because that’s the image they have of them in their head, that’s how they are. Young, gorgeous, stuck in aspic at 28. Or whenever. I mean, I get it. I do. Audrey Hepburn in Breakfast at Tiffany’s (31, almost geriatric) is a picture editor no-brainer. Compared to, say, Audrey Hepburn aged 63 (and still absolutely bloody stunning, for what it’s worth) doing charitable work for Unicef.

The truth is rooted in society’s notions of what’s attractive and, regardless of all the lip service that might get paid, the reality is that youth is always always considered more attractive. Why else would so many of us spend so much trying to preserve it.

You can envisage the conversation – there’s probably several going on right now in offices around the world – ‘I’ve got this picture of her at 60, or this one of her at 27.’ ‘Let’s go for the one where she’s 27. Everyone will recognise her. And, I mean, look at her jowls/waist/wrinkles in that one.’ And I’m not blaming anyone for that, I do it every morning in the bathroom mirror.

But what bothers me most is the erasure. The idea that no matter what we’ve achieved, and how long we kept achieving it (or even didn’t. That’s a whole other post, but when are we going to stop valuing people and ourselves solely by their/our output?) our value starts to ebb away at 30. Thirty five tops.

Because, if you allow yourself to be led by the images used on their obituaries, Marianne Faithfull mainly existed tangentially to Mick Jagger and if she produced anything of worth after Broken English (1979, with a second, Thelma & Louise related, wave in 1991) you could be forgiven for not knowing about it. Tina Turner, despite being immensely successful in her fifties and sixties and beyond, is trapped as the woman with haunted eyes performing alongside her abusive ex-husband Ike. Sinead O’Connor is forever the gamine genius who turned Nothing Compares To You into an anthem. Her subsequent struggles forgotten, because who really wants to look at those. Jane Birkin, the waif-like muse of Serge Gainsbourg and je t’aime fame, not the singer, artist and performer with an iconic bag named after her. Annie Nightingale, John Peel’s protégée not the woman who broke a thousand glass soundbooths for women behind the decks. Shirley Conran, who wrote Lace in her late 40s, Superwoman in her 50s and founded The Work/Life Balance Trust, amongst many other things, is pictured as a ‘dollybird’ reclining on a sofa.

There are quite literally a million more examples. But the point, I think, is this: pictures, images, matter. (When journalists stick with a byline picture taken at 30 when they’re 50, they know what they’re doing, because they do it to other people all the time. It’s not laziness or because they’ve risen above such boring visual representations, it’s because they understand how society works and they’d rather be laughed at than admit to knocking on a bit.)

The image we choose to use to illustrate a piece speaks volume. The image we choose to use to illustrate a life far more so. Every time we use an image that erases 50 years we do exactly that, erase 50 years. And with it the work, the love, the labours, the loss, the joy, the achievements, the failures. The life. As if everything achieved in those decades has less value than whatever came before.

So let’s hear it for Iris Apfel (below), the only example I could find of a woman who has been preserved in aspic at 101.

I love this. I have several friends who knew her, so I’ve seen quite a few photos of her from more recent times. But what strikes me most reading this is how much I hate photos of myself that show my age. I do not want to judge myself for aging and do anyway.

This internalization of something so brutal in our culture doesn’t make me happy. It’s a running theme in my life.

Thanks for writing such a great piece.

I love this post Sam. A truly great picture of her, glowing from the inside out.